Residents and Advocates Demand a Warehouse Moratorium for a “Region in Crisis”

Photos by Sadie Scott

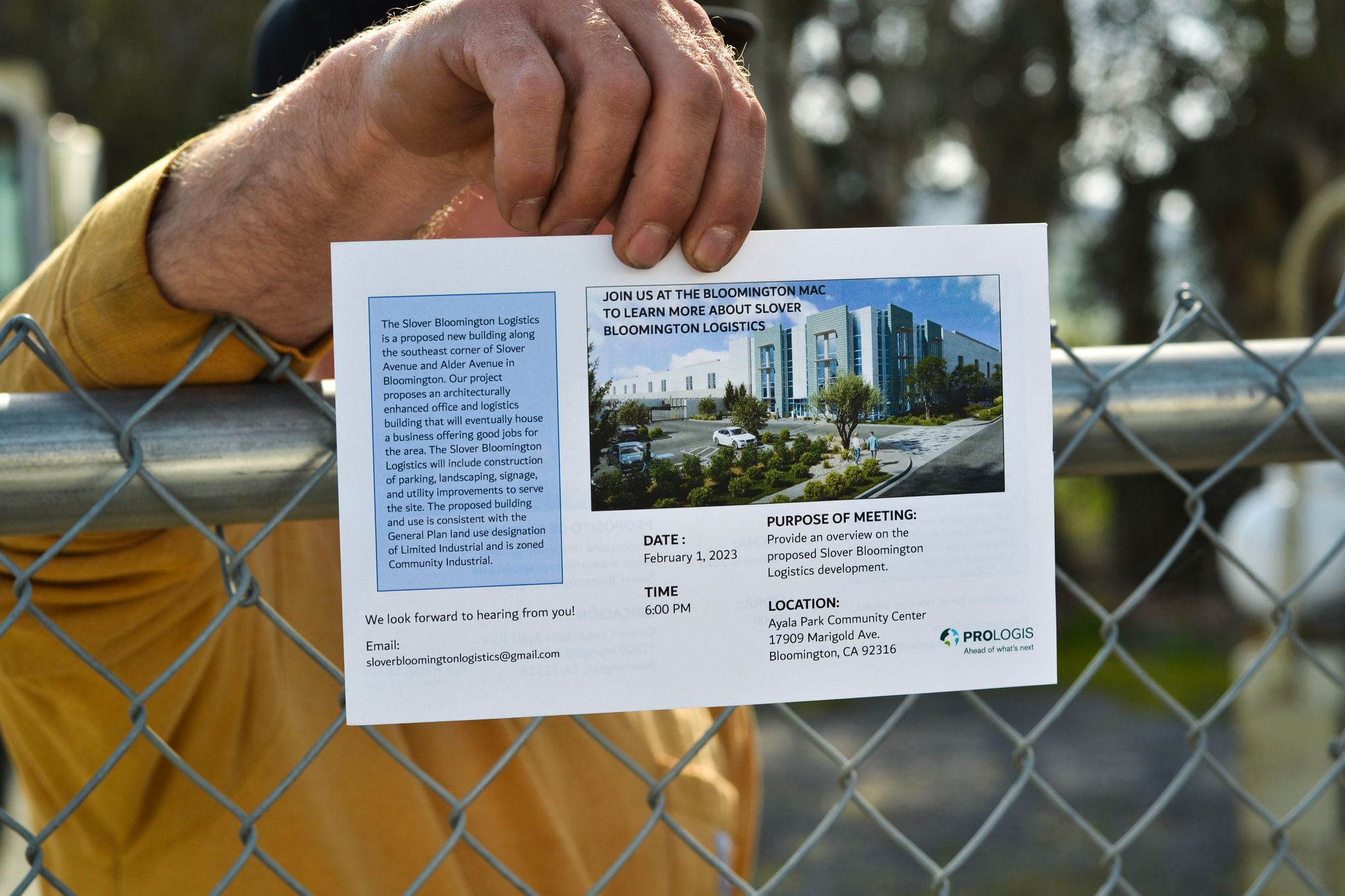

If you stand at the cul-de-sac end of Otilla Street in Bloomington, you will see large tan-colored suburban-style homes adorned with solar panels, and you likely can’t miss the large Amazon warehouse that looms in the background.

Only a few hundred feet and a black metal fence separate the warehouse from the nearby residential community. The DUR8 Delivery Station sits on the intersection of Slover and Laurel Avenues, about half a mile north of nearby Bloomington High School.

An additional 213 acres of planned warehouse space will bring increased truck traffic and air pollution to the unincorporated community already fraught with warehouse-related emissions.

“We just want a quality of life that’s better than warehouses, that’s better than the logistics industry taking over our lives,” school teacher and Bloomington resident Caitlin Towne told The Frontline Observer last November after county leaders adopted the Bloomington Business Park Specific Plan. “We shouldn’t have to worry about warehouses shadowing schools and kids walking past trucks every single day.”

About one billion square feet of the Inland Empire’s land is occupied by warehouses and about 170 million square feet has been approved or is in construction pending for warehouse operation. That’s according to a letter and an accompanying “Region in Crisis” report that a coalition of 60-some environmental, labor, academic and community organizations sent to Gov. Gavin Newsom and other top state lawmakers in late January.

Signatories to the letter are calling on California to declare “a state of emergency and public health crisis in the Inland Empire” and are urging Newsom to issue a one-to-two year pause on the construction of warehouses in the region. On Wednesday, advocates with the Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice (CCAEJ), the Robert Redford Conservancy for Southern California Sustainability, Riverside Neighbors Opposed to Warehouse Development (RNOW) and others met with representatives from Newsom’s office to discuss their report and ask for state intervention.

“What we’re asking for is pretty clear and is laid out in detail in the [Region in Crisis] report,” said Joaquin Castillejos, a Bloomington-based community organizer with CCAEJ. “I hope this engagement with the Governor is a turning point for our community.”

60 groups statewide are declaring the issue of warehouse pollution a public health crisis. In a report/letter to @GavinNewsom @RobBonta, @CCAEJ @rrconservancy @scsangorgonio are demanding a 2-year regional warehouse moratorium to allow time for solutions to be implemented. pic.twitter.com/IlbKP1Ehd1

— The Frontline Observer (@FrontlineNewsCA) February 8, 2023

The report notes that the region’s existing 4,000 warehouses generate 15 billion pounds of carbon dioxide pollution annually, which has severe consequences for people living near these facilities and other freight hubs.

“The statistics we found have been shocking,” said Susan Phillips, director of the Robert Redford Conservancy. “The issue is severe in that the number of warehouses is staggering — to the point of almost being unbelievable.”

Diesel trucks used to distribute goods via the warehouse and freight network produce nitrogen oxide (NOx) and particle pollution that combines with sunlight to form smog (ozone). This type of pollution can be devastating for children, seniors and people living in low-income communities of color.

With diesel exhaust emitted by delivery trucks constantly driving in and out of the vicinity, the significantly higher cancer risk for those located near warehouse clusters concerns, sickens and angers IE residents but does not surprise those exposed.

“The fact that they go by schools, very close to schools, causes higher levels of asthma and other kinds of chronic illness, even heart disease, which has been linked to a higher likelihood of getting infected with COVID, certainly premature death,” Jim Bloyd, coordinator for the Collaborative for Health Equity based in Chicago, Illinois, said about the diesel trucks.

Climate justice journalism has previously called attention to the way families in the IE have been “treated like sacrifices,” and the letter to Newsom highlights the particular impact on children living near warehouses who suffer from asthma, nosebleeds and illness requiring hospitalization at alarming rates.

Despite these harms, developers continue to build close to residential areas.

About 300 warehouses are 1,000 feet or less from 189 schools in the region. As these facilities increase at five times the rate of population growth, authors of the letter estimate the newly approved and pending warehouse space could result in a 10 percent increase in carbon emissions in just a few years.

“These projects are approved without pushback without questions asked about the cumulative and public health impacts,” said Hallie Kutak, a staff attorney and senior conservation advocate with the Center for Biological Diversity who signed the letter. “The need for this pause and regional moratorium is really to give elected officials the time to figure out how to tackle this problem. There are so many available mitigation measures, public health measures [and] protective tools that could be implemented to keep people safe — and not just mitigation, but also planning and land use decisions to ensure that these warehouses are kept in areas separate from residential neighborhoods.”

Phillips called the meeting with Governor Newsom’s office “preliminary and productive” and hopes that conversations between state officials and environmental justice communities in the region will continue.

“We want to have a conversation with our local officials, but we simply just can’t,” said Phillips in a phone interview with The Frontline Observer on Wednesday. “It is a tragedy of democracy.”

Daniel Villaseñor, deputy press secretary for Governor Newsom, shared that the state is taking action to address air quality in communities like the Inland Empire hit hardest by pollution by adopting clean truck rules and making investments in local level climate projects.

“California is taking urgent action to clean the air in communities hardest hit by pollution,” Villaseñor shared in an emailed statement.

Interventions to Address the Crisis

Kutak sees realistic prospects for a regional warehouse moratorium.

The cities of Chino, Colton, Jurupa Valley, Pomona, Redlands and others have implemented warehouse restrictions in the last few years. In some cases, local planning agencies have used temporary pauses to make health and land use assessments, and some have adopted ordinances to reduce health impacts from diesel trucks.

Precedents exist for addressing public health concerns at the regional and local levels.

In Chicago, Bloyd participated in a campaign that stopped a polluting metal shredding operation from relocating from an affluent white neighborhood to a working-class Black and Latino community. He sees a struggle similar against exploitation and environmental racism brewing in Inland Southern California, which is why he lent his signature to the coalition’s request for a moratorium and other interventions.

Authors of the letter want external oversight from a Department of Justice attorney when warehouse projects are initiated.

The attorney general has previously issued informal guidance regarding best practices for warehouse projects, Kutak said, but no clear mandate from the legislature currently exists that would compel the AG to intervene when projects fail to meet requirements.

“Giving the AG clear guidance on when and what to enforce is one of many needed interventions in the Inland Empire,” she said. “It’s not that the AG does not have the authority, but it needs a mandate. It's clear, the data shows in this letter, the state’s just not doing enough. We have all these local jurisdictions that are making their own local land use development decisions without consideration for how those decisions play into the cumulative impact, and that's where the state can come in.”

In addition to imploring the state to earmark “funds to preserve Inland greenspace,” which Kutak said is “rapidly disappearing,” along with funds for “biodiversity, habitat, and farmland—all of which are linked to community health, pollution remediation, carbon sequestration, and climate resilience,” the letter she signed also asks for prohibition of developer donations to members of city councils and decision-makers within three years of decisions pending on projects and calls for enforcement of campaign contribution limits established via AB 571.

“AB 571 makes it a misdemeanor for elected officials to accept donations while a license or permit decision is pending and for some time after the decision has been made,” Kutak said. “There are instances in which officials have accepted donations above and beyond what AB 571 allows, and when they do accept donations in excess of that amount, they are in violation of AB 571.”

The Role Community and Labor Organizations Can and Do Play

Another intervention spelled out for Newsom and state officials would entail collaborative work with community groups and schools to determine standards and funding to support community health in impacted areas.

“At the Garcia Center for the Arts, we have come to realize that warehouses are playing a major impact in the degradation of our community's health, through the scourge of trailer congestion, air pollution, displacement of residents, and strenuous low quality employment that does not ensure long-term security for the workers,” explained Jorge Osvaldo Heredia, the executive director of the arts space who also signed the letter. “This is important to us as the Garcia Center because we are involved in the work of enriching our community through the promotion of the humanities and culture. We see the need for a diverse economy that promotes creativity, and thinks outside the box that is logistics warehousing.”

Heredia’s community has tried to cultivate awareness about pressing ecological concerns by planting 40 trees around the Garcia Center and by curating a “Life and Logistics in San Bernardino” community art gallery at the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art in Riverside.

Kutak said IE communities on the frontlines are also in the best position to provide input. She helped file a lawsuit against the county of San Bernardino after warehouse approval in Bloomington prompted plans to relocate an elementary school to accommodate development.

Amid the litigation, residents in the area have been organizing against warehouse projects.

Making documents available in Spanish — the primary language of some of the impacted communities — establishing bodies akin to tribal councils, and using other legal mechanisms, could further incorporate community concerns into industrial projects, Kutak said.

Signatories to the letter also support input from labor.

In turn, Sheheryar Kaoosji, executive director of the Warehouse Workers Resource Center, said his organization has been heavily involved in the call for community benefits.

“We've had a lot of our members and workers over the years come down with cancers way before the age when you'd expect that, [along with] other kinds of ailments,” he lamented. “A lot of our workers have children who deal with asthma. So obviously, people who work in this community also have to live in this community.”

From Ontario, to Fontana, to Moreno Valley, to Perris, to San Bernardino and throughout inland geographies where the warehouse-heavy economy attracts residents in search of paychecks, permanent disability and chronic respiratory illness abound, and Kaoosji said the IE workplaces he helps organize have injury rates as high as 10 to 15 per 100 employees.

“That's devastating to working-class community,” he said, later emphasizing: “That’s just unnecessary. That’s, again, all part of the same system that leads to air quality issues; [it’s] the same system that leads to health and safety issues inside of a facility — companies cutting corners and looking toward profits instead of looking toward the community that they're benefiting from. So I think taking a holistic approach is what is needed.”

Anthony Victoria contributed to this story.