In the midst of changing landscape, Bloomington residents plan to fight back

Editor's Note: This story was updated on Thursday Jan. 5, 2023 to include more details about the Bloomington cabalgatas (horseback rides).

Every year during Black Friday, online shoppers rush to seize on “once in a lifetime” deals for clothing, sporting goods and electronics as they reminisce in the afterglow of Thanksgiving about what they are grateful for.

While this holiday represents packaged bliss for most shoppers and big bucks for Amazon and other retail giants, not everyone sees the same benefits.

To residents of communities like Bloomington, California, where parks, schools and homes are being torn down to make room for more warehouses, this holiday is a hard reminder of the stark differences in treatment that communities of color face in comparison to their predominantly white counterparts. For example, an analysis done by Consumer Reports found that Amazon warehouses are disproportionately likely to be built in communities of color struggling with poverty.

Residents of unincorporated Bloomington recently swallowed a bitter pill when the Bloomington Business Park Specific Plan—a 213-acre plan to rezone agricultural and residential land into industrial and commercial land—was approved by the San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors on Nov. 15 despite widespread opposition. The decision is part of an ongoing push by local governments and developers to increase warehouse space in the area to meet the demands of e-commerce.

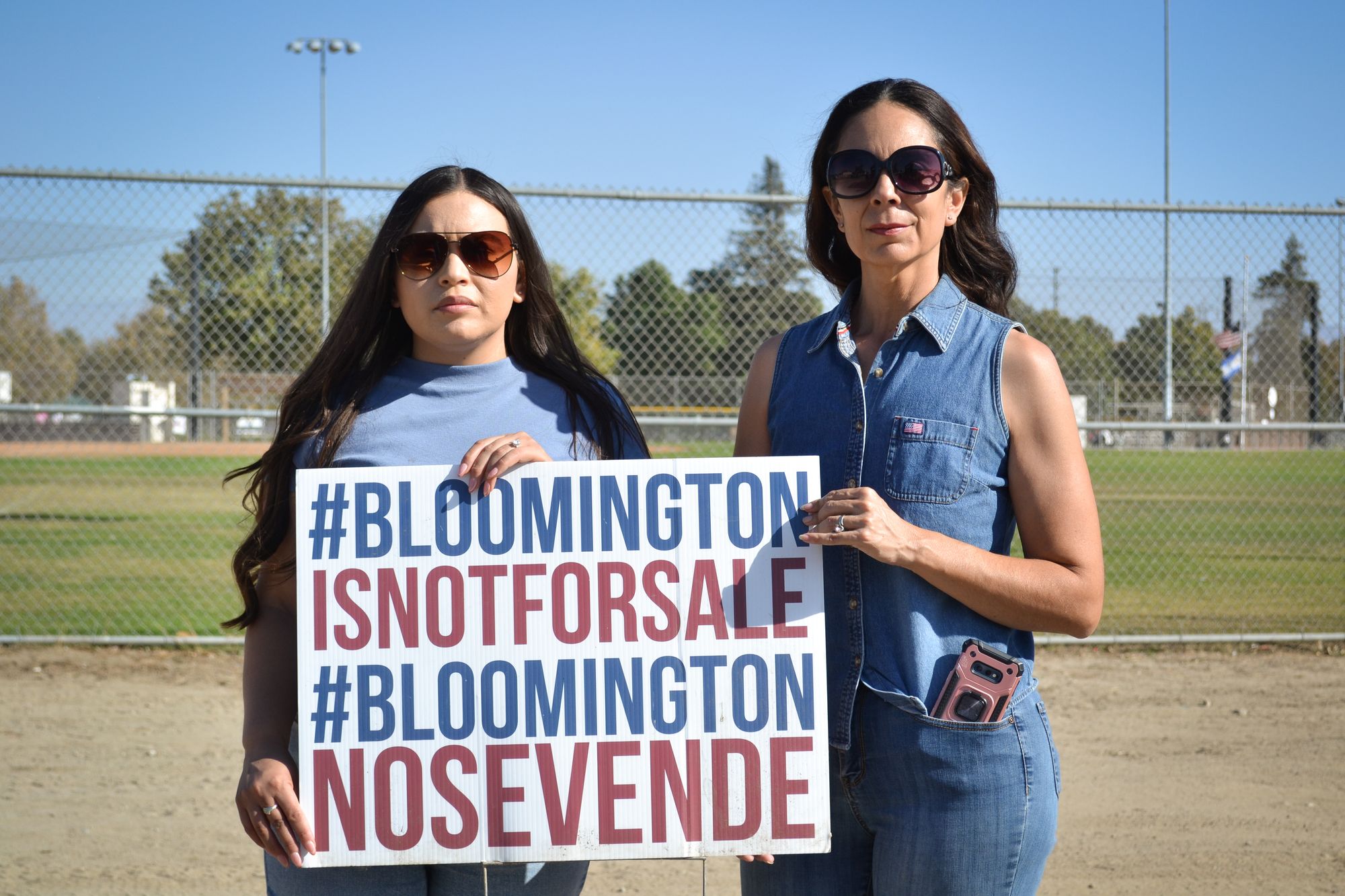

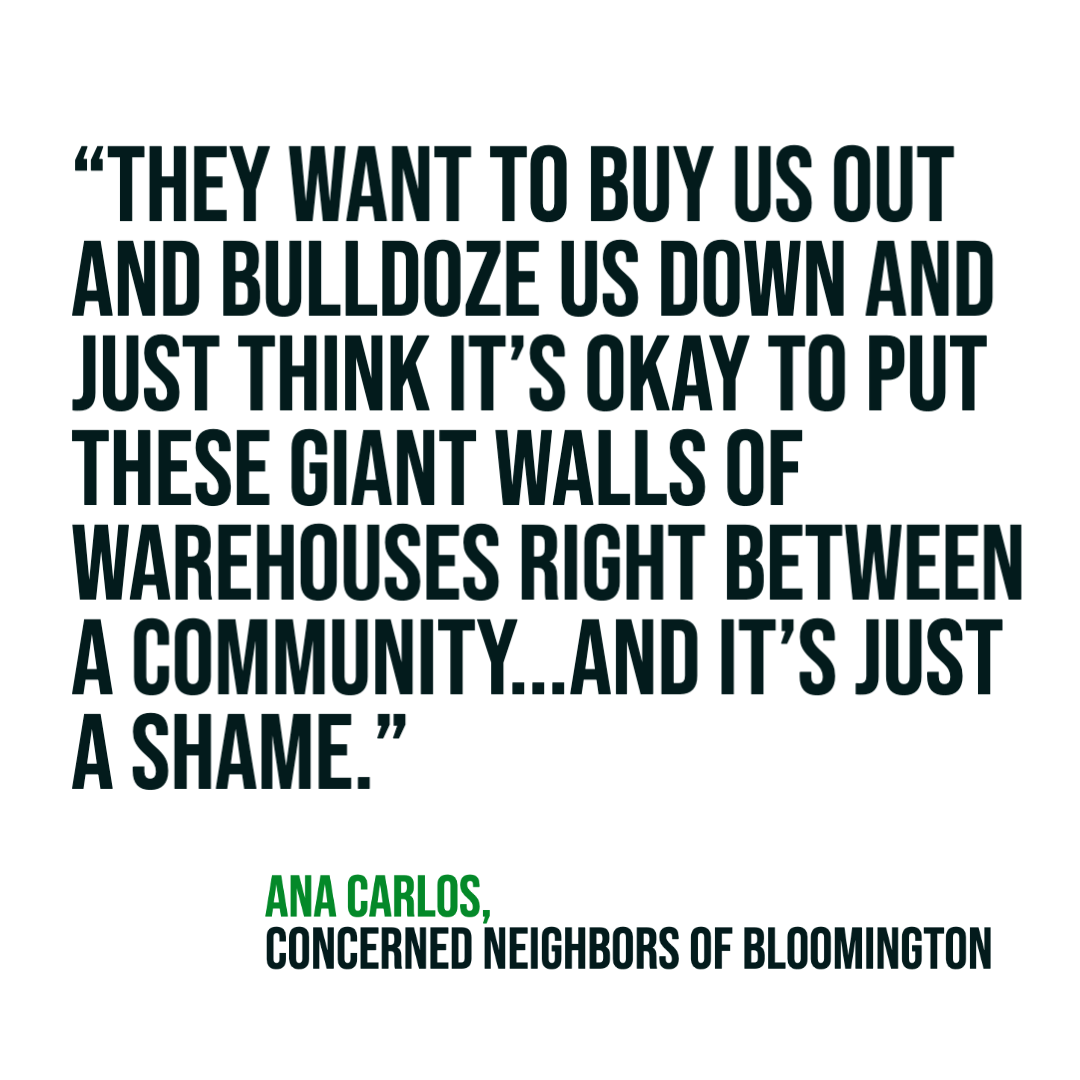

“This has been called cheap land by, you know, these large corporations that want to come in,” says Ana Carlos, a long-time resident of Bloomington and member of community organization Concerned Neighbors of Bloomington (CNB). Concerned Neighbors of Bloomington has been organizing for years against the expansion of warehousing in Bloomington. “They want to buy us out and bulldoze us down and just think it's okay to put these, you know, giant walls of warehouses right between a community because it's not even on the side of town. It's right in the middle of our neighborhoods. And it's just a shame.”

CNB has offered residents like Ana an avenue for building community by speaking with residents about warehouse-related environmental and health research findings, hosting informational events and organizing around Municipal Advisory Council meetings. They have also established strategic partnerships with other community organizations like the Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice (CCAEJ) and the People's Collective for Environmental Justice (PC4EJ) that CNB says are necessary in order to come face-to-face with local government and developers.

To prepare and encourage neighbors to attend the Board of Supervisors meeting, Bloomington residents from community organizations including CNB, CCAEJ, and the Inland Coalition for Immigrant Justice (IC4IJ) hosted a cabalgata on Nov. 6. Nearly 100 men on horseback, many in charro regalia, were joined by their children and families who carried signs and sang as the cabalgata processed through the streets of Bloomington.

Rhythmic beats of horse hooves on street pavement, music and chants filled the air of south Bloomington past houses and greenspace that will soon be warehouses. These cabalgatas are led and coordinated by CCAEJ organizer Joaquin Castillejos, who became inspired by similar efforts in nearby Mira Loma.

Residents that showed up to support the event expressed a variety of feelings about the state of their community.

“Once you start telling people what's actually going on in the neighborhood, then people start to see: Oh, this isn't a good thing. You know, maybe we should pay more attention. We should get more involved with the community,” says Ben, a nearby resident who showed up to support the event.

He shared some of the ways the large influx of warehousing is already impacting residents. “It’s less walkable, less bikeable. Now we have big warehouses next to schools. It's just, overall, a decrease in the standards of living as far as I see it. People talk about all this money coming in, but I really don't see an improvement to the lives of the average citizen.”

He is not alone in this sentiment. Anthony Noriega, district 5 director of the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) de Inland Empire, believes that the harms caused by warehouses do not just occur outside of their walls, but within them as well due to low paying jobs with no union associations, benefits or long-term career paths.

“We got a double whammy… We've been hit with the warehouses that are taking away from the ranch lands and the farming lands that we historically have had and then we also now are stuck with these low paying jobs,” says Anthony. Given the Inland Empire’s increasingly industrial economy in the past decade, many residents who would have previously grown into agricultural work have been pushed into the logistics industry from as young as ninth grade onwards. “Historically, in the minority communities, we already have a direct pipeline going from high school to the prisons, okay? And now we have a direct pipeline going from the high schools to the warehouse industries.”

Companies like Amazon recruit young workers for their warehouses, but employees often don’t stick around, especially as they age and begin to feel the physical demands of the labor, says Jasmine Cunningham, the treasurer of allied group South Fontana Concerned Citizens Coalition and a member of CCAEJ. A 2021 report from the New York Times found that Amazon's turnover rate was roughly 150 percent annually among hourly employees––about double the industry average.

For Ana, moving to Bloomington was a dream come true. It allowed her family to own a home, while creating a semblance of her parent’s Mexican culture in her own backyard.

“My parents are from Mexico and so every summer we would go back,” shares Ana. “The ranch, the farm lifestyle—it's a cultural thing for us. So when we were able to find our little two acres in Bloomington, it was for us to be homeowners, of course, but to also have our children raised, you know, with our traditions. It was just a dream come true.”

But now, she believes her community is facing an existential crisis that is too balanced in favor of developers who she says don’t care about the small town.

“When you stick a warehouse right in front of an elementary school… it's giving them a glimpse of their future,” she says. “So what is the future? Are they warehouses? Is it, you know, all these trucks coming in and out of their neighborhood? The noise pollution it makes? I don't think it's fair. The people who vote to allow these developments in our neighborhood, I don't think they would allow these kinds of developments in their neighborhood or next to their children's schools.”

Nonetheless, the people who continue to call Bloomington home are not giving up. The equestrian lifestyle of owning ranches and livestock remains vibrant in the face of a changing environment. And residents are making it clear that they will continue to fight back.

“This is demonstrating our resilience, you know? This demonstrates our commitment to the community,” says Concerned Neighbors of Bloomington member Alejandra Gonzalez. “There's neighbors like Ana and Joaquin [Castillejos] and people that we've met just because we have no agenda other than to be able to keep our homes and keep our family and keep our [equestrian] lifestyle.”