Riverside residents briefly celebrate as controversial warehouse project is shelved

Community outcry results in a pause for West Campus Upper Plateau Project, but concerns remain about future warehouse development

Originally published for The Riversider Magazine's August/September Issue

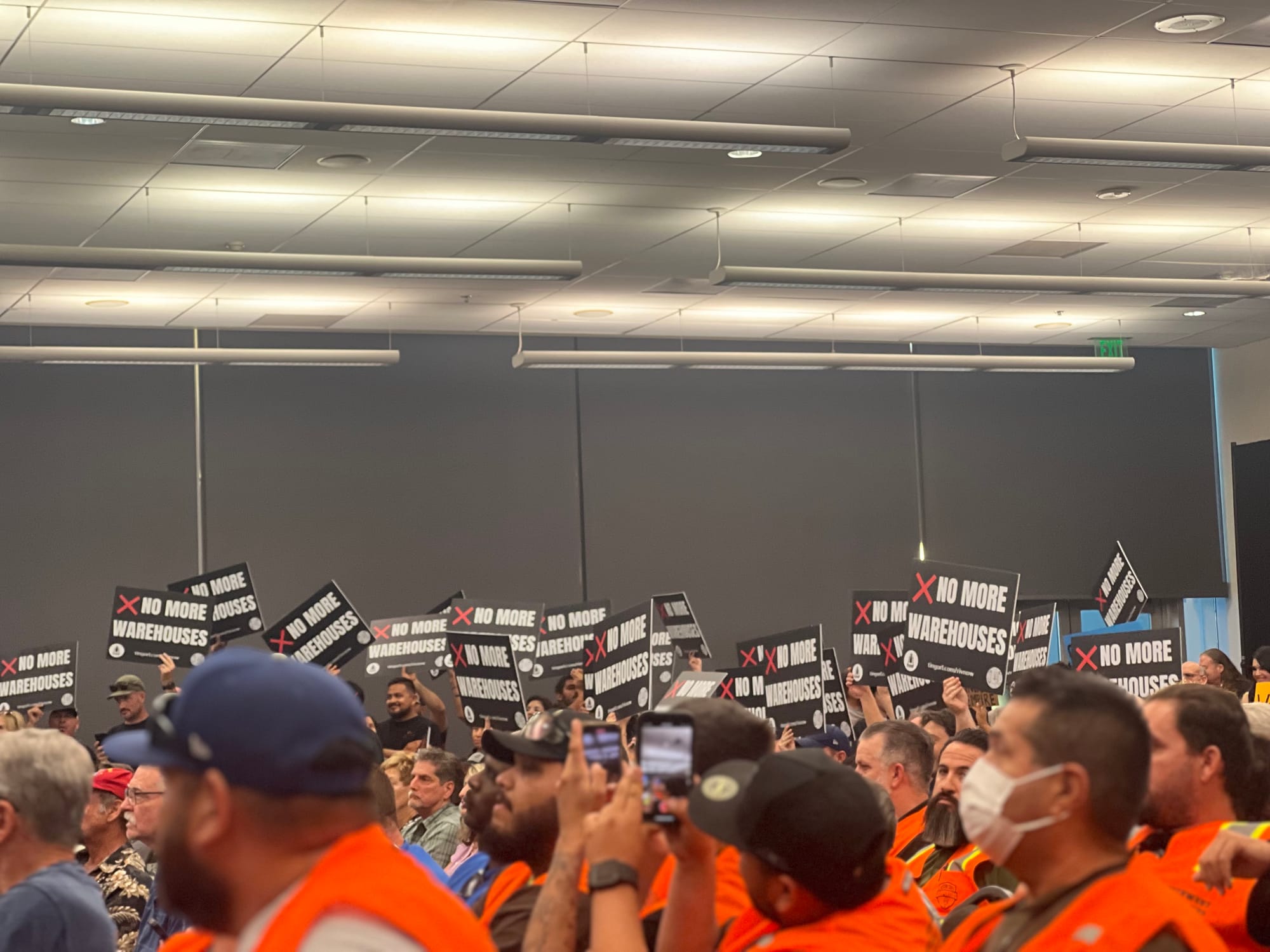

Jennifer Larratt-Smith and Riverside Neighbors Opposing Warehousing (R-NOW) were ecstatic, yet somewhat perplexed, after a lengthy public hearing on June 12.

The March Joint Powers Authority (March JPA), which oversees large swaths of land in Riverside, Moreno Valley, and Perris—designated for warehouse development near the former March Air Force Base—voted 6-1 to remove the controversial West Campus Upper Plateau Project from its agenda.

The project, proposed by Upland-based real estate firm Lewis Group of Companies, aimed to construct 1.8 million square feet of warehouse space on 800 acres of land near Riverside’s Orangecrest and Mission Grove neighborhoods.

Larratt-Smith and R-NOW, who had rallied over a hundred people to fill the Moreno Valley Civic Center, viewed this turnout as a significant victory.

“We fully expected the commission to vote in favor,” Larratt-Smith said. “So we’re really glad they acknowledged the community’s concerns and took it off the agenda.”

However, she remains cautious. The pause does not guarantee a permanent halt, as the March JPA could potentially revive the project with a majority vote.

“We’re kind of waiting,” Larratt-Smith said. “We’re sure that behind the scenes, the developer and the JPA staff are figuring out their next steps. We don’t think they’ll just walk away.”

Feeding the E-Commerce appetite

The land in question, near Mission Grove and Orangecrest, was not always designated for warehouses. In 1918, the U.S. military established the Alessandro Flying Training Field, later renamed March Air Force Base, which played a crucial role in supporting both World Wars. The base contributed to Riverside County’s economic growth and trained numerous air force pilots.

In the 1990s, the base was re-designated as a reserve installation, leaving thousands of acres open for development. The March JPA’s initial vision for the land included a mix of housing, commercial, and industrial uses, with plans for preserving open space, a medical campus, and residential areas to accommodate Riverside County’s growing population.

However, much of the development within a 5 mile radius of the Orangecrest, Mission Grove, and the March Reserve Base has focused on warehousing. This shift is largely driven by the demand for online shopping and the desire to boost regional economic growth. Public data from the Warehouse CITY research tool shows approximately 200 existing warehouses , with 13 either under construction or in planning stages. Nine are under environmental review, and 13 are currently vacant.

At the June 12th meeting, Adam Collier of Lewis Group presented the West Campus Upper Plateau Project as aligned with March JPA’s economic and environmental goals. He highlighted promises of clean vehicle infrastructure, a $30 million community park, a $10 million fire station, and job creation. Collier emphasized that the project’s benefits included plans for solar-powered infrastructure and recycled water systems, as well as preserving existing hiking and biking trails.

Dan Fairbanks, March JPA’s planning director, noted that the project’s commitments fulfill an early 2000s legal settlement with the Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice (CCAEJ). This agreement required guarantees for a public park and natural preservation.

Despite these assurances, many speakers, including Orangecrest resident Sandy Cabrera, voiced frustration over the potential environmental impact. “Why surround sensitive areas with warehouses and exacerbate health problems like asthma and cancer?” Cabrera asked. “Are you going to act as ruthless politicians or conscientious human beings concerned with the health and safety of your community?”

A tarnished reputation for March JPA?

Larratt-Smith and her neighbor Michael McCarthy helped form R-NOW in response to the surge in warehouse developments near Orangecrest and Mission Grove. They are now regular attendees at March JPA meetings and city hearings.

They both criticize March JPA officials for alleged bias and lack of transparency. In 2022 , they challenged Riverside Councilman and March JPA commissioner Chuck Condor for allegedly supporting the Lewis Group during a Board of Ethics hearing.

“We’ve been working steadily for two years, making all kinds of noise, but we’ve been completely dismissed,” Larratt-Smith said. “If you care about your community and want to make a difference, you have to be very engaged.”

McCarthy, who developed the Warehouse CITY research tool, argues that the warehouse boom has worsened air quality, with Riverside and San Bernardino counties ranking among the worst for smog pollution. The West Campus Upper Plateau Project is expected to generate around 35,000 vehicle trips daily.

“There are structural forces pushing warehousing as the economic engine,” McCarthy said. “But we need to change that narrative. This isn’t the only means of growth.”

McCarthy points to a Riverside County Grand Jury investigation that criticized the March JPA for its public transparency. The report concluded that while the agency generally complies with legal requirements, its transparency is minimal.

“The Grand Jury found that the March JPA follows the letter of the law but not the spirit,” reads part of the investigation’s executive summary. “In some cases, it is out of compliance with the law. The March JPA’s transparency is limited to what is minimally required.”

McCarthy and Larratt-Smith argue that the March JPA’s actions undermine local communities, which should benefit from the redevelopment of public land but instead face worsening environmental conditions.

“March JPA will be associated with poor environmental policies and warehouses because they don’t engage with the people who live here,” McCarthy said.

Dr. Grace Martin, March JPA’s CEO, responded in an email, stating, “[March JPA] addresses health and safety concerns through responsible land use planning and compliance with federal, state, and local regulations within our jurisdiction, and through coordination with neighboring cities and the county.”

Collier did not respond to requests for comment.

What’s next for Orangecrest and Mission Grove?

With the March JPA scheduled to sunset by July next year, the agency is taking public feedback on an environmental justice element. McCarthy expresses skepticism about this transition, believing it may not lead to meaningful change and that the agency avoids responsibility at the community’s expense.

“They do things that are lower quality than any of the surrounding jurisdictions,” he said. “Warehouse growth is as unifying an issue as there is in our neighborhood and politics in general today, and they're ignoring us. So when they say they have a civic engagement policy as part of their environmental justice element, it's just laughable.”

Larratt-Smith is glad the agency is scheduled to sunset, but is concerned about what’s in store for the acres of land that border her backyard. And she’s remaining vigilant about the decision makers countywide that might continue what she considers a greedy pattern.

“The March JPA is terrible, but they're not the only ones that are terrible,” says Larratt-Smith. “There are all kinds of projects being passed and approved, and people are in a warehouse frenzy because developers are greedy, and our politicians let them do what they want. People with money have power over those who govern. But because that’s the case, the community has to stand up for the community. We have to do something and we have to act.”

As the future of Orangecrest and Mission Grove hangs in the balance, residents remain committed to their cause. They continue to push back against large-scale warehouse developments, advocating for a community-centered approach that prioritizes health, safety, and the environment.

The battle against the West Campus Upper Plateau Project is just one chapter in their ongoing fight to shape the future of their neighborhoods.

This story was originally published in The Riversider Magazine and is republished online with their permission