COMMENTARY: ‘You can depend on my solidarity’: My experiences as an Inland Empire warehouse worker

The following first person narrative is being shared by a warehouse worker concerned about potential retaliation. To protect his identity, the author has decided to write under a pen name

There's a lot of controversy around the logistics industry’s active role in polluting the environment, creating harsh conditions for employees, underpaying staff and not following proper COVID regulations. I’ve experienced this all firsthand, as a warehouse worker and a resident of California’s Inland Empire. Our region is disproportionately and negatively impacted by companies that have used our backyards to draw their labor force, build their massive warehouses and degrade the air quality in favor of profit margins.

I am writing this first-person account of my experiences as a warehouse worker to give readers an in-depth look at the lives of people impacted by the logistics industry – our region’s biggest industrial sector. To protect my identity and reduce the risk of endangering the employment and lives of my colleagues, I will be writing this under the name, Niño de la Tierra.

I believe it is important for us to band together, share our experiences as warehouse workers, voice our concerns and disagreement and use both research and lived experience to illustrate the long-term negative consequences of free shipping.

‘Routines and Reminders that this is best for now’

My father and I start the day at 4:45 AM. Our daily blaring alarm serves as the constant reminder that it’s time to get ready for work.

Four days out of the week there’s a similar routine. I hear dad in the kitchen making himself his morning cup of coffee, which unlike mine is heavy on the sugar, light on the milk. I drink mine black with a hint of sugar, pan dulce on the side.

We live and work in Moreno Valley, California, a growing community that is now the second largest city in Riverside County. We are a part of the large majority of Latinx people that account for half of the local warehouse workforce. In fact, warehouse jobs are so common here that entire neighborhoods, including ours, are surrounded by them.

Like many immigrant families, my father and mother have juggled multiple jobs to support my education. Yet, despite obtaining a Bachelor’s Degree, I find myself in the same place I was when I got my first job six years ago in the summer of 2016 – working inside a warehouse. It feels disappointing, and sometimes, I feel like a failure. I know I’m not alone. There aren’t many options available for college graduates other than logistics jobs for a quick salary. It feels unfair, but nonetheless, I stick through it because my father reassures me that it’s best for now.

I put my worries aside to finish my cafecito and pan dulce and say goodbye to my dad. “Que dios te acompañe (god be with you),” he says to me before we part ways. Before I punch the clock at work, I spend my 10 minute work commute bumping the usual norteño, corrido, banda or rap song.

Once I get to the warehouse, I usually see a myriad of people – some happy to be there, others dreading the early morning and others seem indifferent. While waiting in line to receive my scanner, I usually greet coworkers and friends before we get our day started.

‘Working with our eye on the clock’

The employment growth for warehouse jobs has doubled in recent years with over 56,000 employees at warehousing and storage facilities in 2019. During the pandemic, many families across the country had to go into a form of survival mode. For people like me, it was applying for a full-time warehouse position due to how easy it is to apply.

They promise more hours, better benefits and higher pay than some retailers, and they make it simple to apply and be accepted. Sometimes, there are no interviews and no need for prior experience, so it appears to be a job that anyone can do.

My job consists of scanning and filling pallets with boxes that arrive on a conveyor. These boxes can be big and heavy or small and light. My job uses a rate system that measures how fast we scan work so I try to stay busy, scanning as many boxes as I can. I take little rest breaks in between, always checking my watch to see if break time is approaching.

During break and lunch, I always sit with the same friends I’ve made at work. We talk about how our day is going and what’s been going on in our lives. It’s a nice moment of relief to just chat and socialize, even if it's for fifteen or thirty minutes.

Sometimes I chat with my coworker Marisol, 46, who works to supplement her family's income. She is like a second mother to me. Marisol is always in a positive mood and constantly speaks with pride about her family. One day during lunch, she spoke about her experiences working at a plastic manufacturing warehouse, “I suffered from very severe allergies since you could inhale the contamination. There were times when I felt burning in my eyes,” she said. “At that time I was given treatment for my allergies because they were very strong.”

At the end of shift, everyone is eager to clock out. We pack together like sardines near the exit, trying to reach the time clock to punch out and go home.

The work can seem easy at first, but over time your body starts to ache and eventually the repetitive task of scanning hundreds of boxes, standing in one spot or occasionally walking throughout your entire shift can have an impact on you. The longer I do the job, the more I lose weight and see a change in my mental state. My desire to socialize has dissipated and I am now more introverted. It's a constant struggle trying to balance work and everyday life outside of the warehouse.

There are times when I wonder if the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) knew of these health concerns and why employers can get away with it. I soon learned that physical tasks that involve twisting or awkwardly moving one’s body could lead to musculoskeletal problems. During the pandemic, OSHA cited Amazon for ergonomic risk factors in a fulfillment warehouse in Washington.

I try to manage by remembering I’m there for money and acknowledging it's a temporary job. I try to remind myself of the sacrifices my family had to make, like leaving behind their home, culture and country to be where we are in life to push me forward.

‘Warehouses impact children like my siblings'

I can’t help but feel concerned when I see warehouses loom over the elementary and middle schools my siblings go to. The thousands of diesel trucks these warehouses attract expose my siblings and other children to diesel particles or other harmful chemicals everyday.

The American Lung Association earlier this year gave both Riverside and San Bernardino counties ‘F’ grades for air quality, while other studies have demonstrated that children living near freight and warehouse hubs tend to have serious respiratory and asthma issues. Over time, respiratory problems may arise within students that attend schools near warehouses.

From the minute I wake up to the time I go to bed, I feel the cycle of violence that comes at the hands of the logistics industry. The reality is, the health impacts aren’t just felt outside warehouse walls, they’re felt inside too.

“We’re just barely making it”

At my job, we’re expected to do a variety of things in different departments. One time, I ended up getting stuck unloading boxes inside scorching cargo trailers. I felt like I was inside a giant, metal oven; this summer, temperatures reached at least 98 degrees. Spending an entire shift in this metal box, I had to be careful not to touch the sides so I didn’t get burned. I cleared my nose at one point after unloading a trailer and the amount of black dust that landed in the Kleenex was more than enough to convince me to switch work departments. I still wonder how much of the dust stayed in my lungs.

Despite the grueling work and awkward moments with some co-workers, there were still small glimpses of humanity. One day during my 15 minute afternoon break I met up with Jason, a 22-year-old Mexican-American young man who was hired two months after me. He applied right after graduating high school.

He described a workplace incident where he was called out by management for simply eating a bag of chips. “Taking a small breather is absurd to them. Being called out for taking little breaks is crazy… I was told to look busy or grab a broom, do something just because standing still was wrong.”

Sadly, incidents like these are common on the floor. From what I see, a lot of folks who work in management don’t have the right demeanor or skillset. It results in them being stressed because they didn’t meet production numbers. As a result, floor leads and other supervisors push their employees even harder to reach that goal, too hard in my mind. Like others before, I’ve witnessed someone faint because their knees were locked for a long period of time.

The presence of labor exploitation is felt deeply by the Latinx community. Around 20% of Latinx residents in the Inland Empire live below the poverty line, as families try to survive on less than $36,000 per year. Despite minimum wage in California being at $15 an hour, the reality is workers need at least to make $22 an hour and work 40 hours per week to rent a two-bedroom apartment.

An Amazon worker I know, described these struggles in a recent conversation. “It would be nice to make enough to not be living paycheck-to-paycheck, to work under better conditions. It's always so hot in the buildings and standing for long hours makes it rough, especially for a one income household. We're just barely making it.” She tells me her 30 minute commute from Hemet to her workplace takes $60 for gas every week.

‘I’m glad my family and I survived’

Working through the pandemic these last two years has been tough. I was one week on the job in a training class when I learned about our site’s first case of COVID. I couldn’t believe it. My coworkers and I had so many questions: What protocols would be set to deal with the virus inside the building? How was the pandemic going to impact our job and pay?

I remember getting home from work that day and having a serious discussion with my parents. I was eventually told by my employer that workers had the option of pursuing unlimited unpaid time off if they chose to stay at home. Because I just got hired and needed money, I hardly took advantage of it. My father didn’t have that option, so he worked his normal hours at the height of the pandemic. While some essential workers had compensation, workers like me were only given one to two dollar raises.

It was a struggle for many of us to stay clear of the virus. Because the Center for Disease Control (CDC) issued mandates on masks and sanitization, we were provided an overview by management about how to protect ourselves. But these weren’t effective since people still became infected. Many workers, including myself, felt management just sort of gave up as more positive cases arose. We were reminded to keep our masks on and to stay six feet apart.

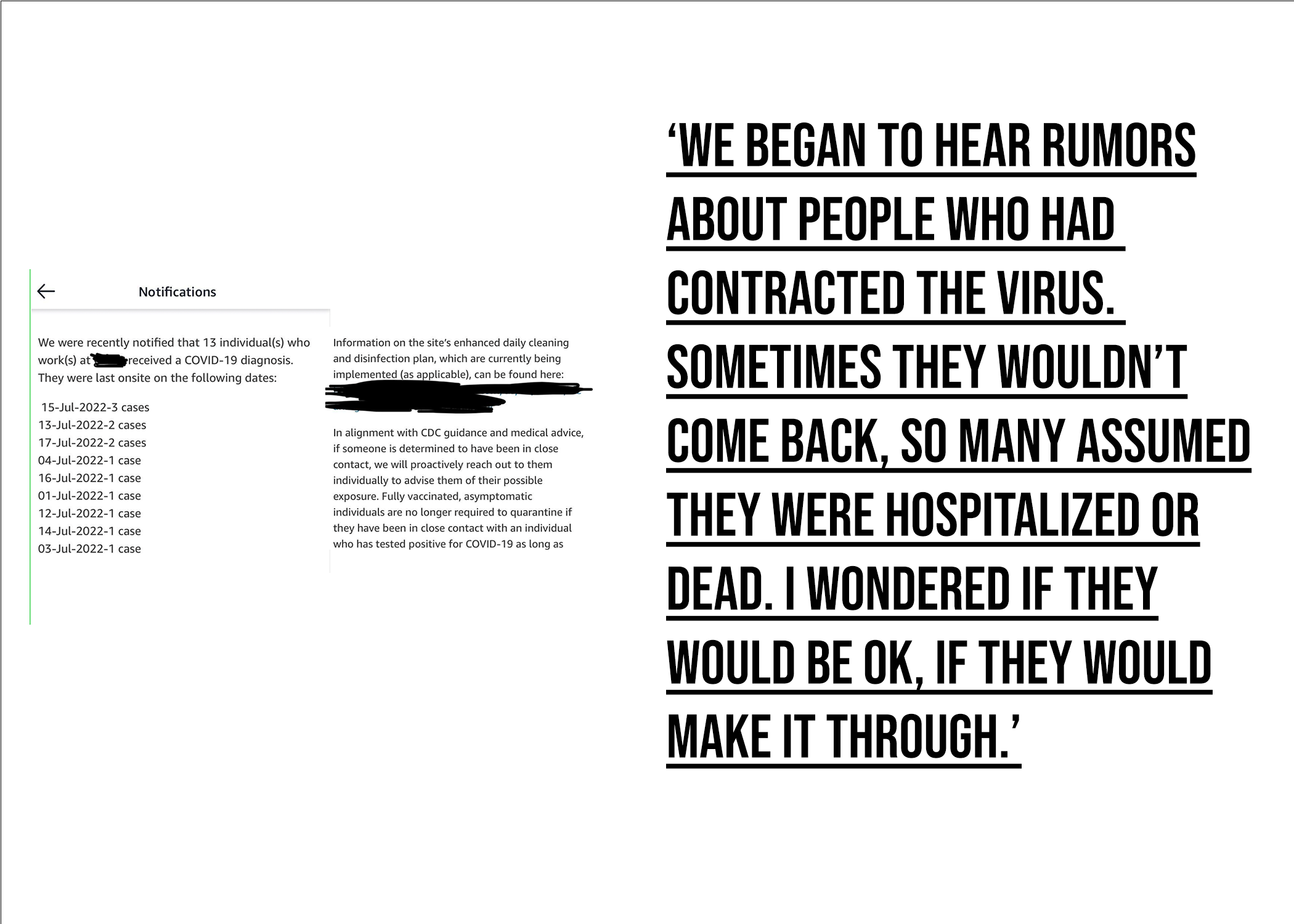

We received phone notifications in the meantime from my employer about the number of employees testing positive for COVID. The information they provided was scarce, so we felt no choice but to carry on.

But things began to change drastically. Soon, plexiglass was installed next to the conveyors to divide us. I constantly heard and saw workers sneeze and cough as we moved items along the belt. Our radios and scanners would be wiped down with clorox wipes after work to accommodate for the next shift coming in. Break rooms and certain workstations were adjusted to meet the six feet rule by skipping a chair or station.

We began to hear rumors about people who had contracted the virus. Sometimes they wouldn’t come back, so many assumed they were hospitalized or dead. I wondered if they would be OK, if they would make it through. Many older employees were never seen again. That's when I knew that this virus was impacting us in real time.

Luckily, we received mandatory COVID testing on site at the time. Those who did test positive received two weeks paid time off. However, in a warehouse that runs 24/7 and contains at least 2,000 employees changing shifts, I had my doubts we were genuinely safe and I felt like it was only a matter of time before I contracted the virus. So as soon as I received the opportunity, I took advantage of my status as an essential worker to receive doses of the vaccine. It was a decision I made to keep me and my family safe.

Earlier this year, I tested positive for COVID. There’s no doubt in my mind that I contracted it while being at work. Soon after, my family was infected too which kicked off feelings of distress, anxiety, fear and guilt.

I felt guilty knowing that I infected them and whatever health issues arised, I would be to blame. We weren't sure what the next two weeks had in store for us but we tried to prepare for the worst by keeping hydrated and well rested. Since we all had COVID, we just quarantined together and waited it out. I’m grateful that our symptoms weren’t life threatening and only flu-like, with headaches that went on for days.

After two weeks, I had to return back to work. I noticed the first few weeks back, I had to catch my breath a few times when moving pallets or being active. I was pissed off that I had to be back at the same place where I caught the virus and be back in the same work routine as if nothing happened. Nonetheless, I reminded myself that I’m fortunate to be here and glad that my family and I survived.

‘“Trabajo es Trabajo” for us. But that can change’

Through my educational and work experience, I’ve learned that ignorance and silence can’t be tolerated. I’m honored to be the children of hardworking immigrants. My parents have taught me to be humble and to be grateful for the opportunities that come.

But I am tired and now I am choosing to speak up. It’s not easy seeing my father wither away and complain about his back pain. It’s tiring to constantly worry about being laid off and having to re-apply for the same logistics jobs for quick money. It’s saddening to see warehouses being built right next to homes and schools. The American Dream should not come with high-anxiety, frustration and broken promises.

As a first-generation resident of the Inland Empire, I feel the responsibility to move ahead and do what’s best for my family and my community. It’s my desire to break the obstacles set in place to keep black and brown people under.

By highlighting the injustices of the logistic industry and through organizing, warehouse workers are showing that it is possible to fight for something better.

Across the country, we are seeing workers risk their jobs to stand up for each other. In New York, Amazon workers gained 55% of warehouse worker votes to create the first union within the company. And now, our region is an epicenter in that fight as well. Recently, a walkout was organized by the Inland Empire Amazon Workers United at an Amazon Air Hub in San Bernardino. It gained national attention because protestors requested a five dollar per hour raise, safer working conditions, and an end to retribution. A five dollar pay raise is a drastic change in financial security. For me and my family, it helps provide more groceries or have some extra after paying utilities like rent.

Only time will tell what the future holds. Working at a warehouse may be the best I can do for now to support myself and my family. I asked my father how he feels about working in a warehouse. He said, “Trabajo es trabajo.” Which is a common outlook of these jobs. Many look at it as something that pays the bills and puts food on the table. An outlook that deserves some understanding, but we shouldn’t really have to be forced to settle for less. History has demonstrated that change is achievable when workers band together.

People are banding together to demand better employment, cleaner air and safer communities. I'm only one of thousands of people who work inside the region's massive sea of warehouses. It is my goal that this first-person experience inspires others to speak up and take action. You can depend on me to be there in solidarity.

This story is part of the local environmental reporting initiative Unfiltered IE that is supported by the civic media project The Listening Post Collective and funded by a grant from the Ford Foundation.